The United Church of Canada recently created a new vision and mission to shape and guide our ministries in the next few years. The three broad headings are Deep Spirituality, Bold Discipleship and Daring Justice. This blog explores those ideas based on current events.

Deep Spirituality

When we come to worship on Sunday, we are moved by music and words, we are reminded of our connection to other people, to the history of the Christian story, and to God’s world. But if only intentionally connect with our spirituality on Sunday morning, we miss opportunities to be deeply grounded in our faith.

Our spirituality is the way in which we connect with God on a daily basis—in between gathering together for worship. Some of us have a regular practice of prayer—maybe in the morning, or at a mealtime, maybe before bed. Some of us have never developed that kind of regular routine. Some of us prefer meditation. Some of us take long walks in nature and notice the changing of the seasons and give thanks for how the earth supports us. Some of us just sit quietly and reflect on life as it goes by. Some of us use music (either listening or creating it) as a way of feeling the spirit move. All of these practices, and many others, help us to deepen our sense of God’s presence so that when something terrible happens in our lives or in the world we know we are not alone.

Sometimes praying might feel empty. We can’t bring back all the people who were killed this week. The words of our prayer won’t change what happened but our deep spirituality reminds us that God comforts those who mourn—ourselves, the families and friends whose lives have changed forever in those moments of violence. Our spirituality reminds us that we are people of death…and resurrection. We are people who know death doesn’t have the last word. Our spirituality reminds us that we are not alone. Our spirituality doesn’t change what is but it gives us strength and courage to stand firm in the God of love, even when the world feels like chaos.

And so we pray in whatever ways we know how. We pray that all those impacted by the school shooting will know the power and strength of love—that they will feel strong arms holding them. We pray that violence will end and that schools will be places of safety, growth and learning.

Bold Discipleship

We ground our lives in our spirituality, our prayer, our vision for the world. Discipleship is about following Jesus faithfully even when it feels counterintuitive or dangerous. In Acts 16, we see Paul act to heal the household worker so her employers could no longer take advantage. It meant beatings and prison for Paul and his companions. Then there’s an earthquake and they could escape but the jailer would have killed himself, so they stayed put and offered him care and compassion in the name of Jesus. They didn’t need to involve themselves in any of this. They could have ignored the household worker as an irritant and carried on. By healing her Paul set in motion a chain of events and had to see it through.

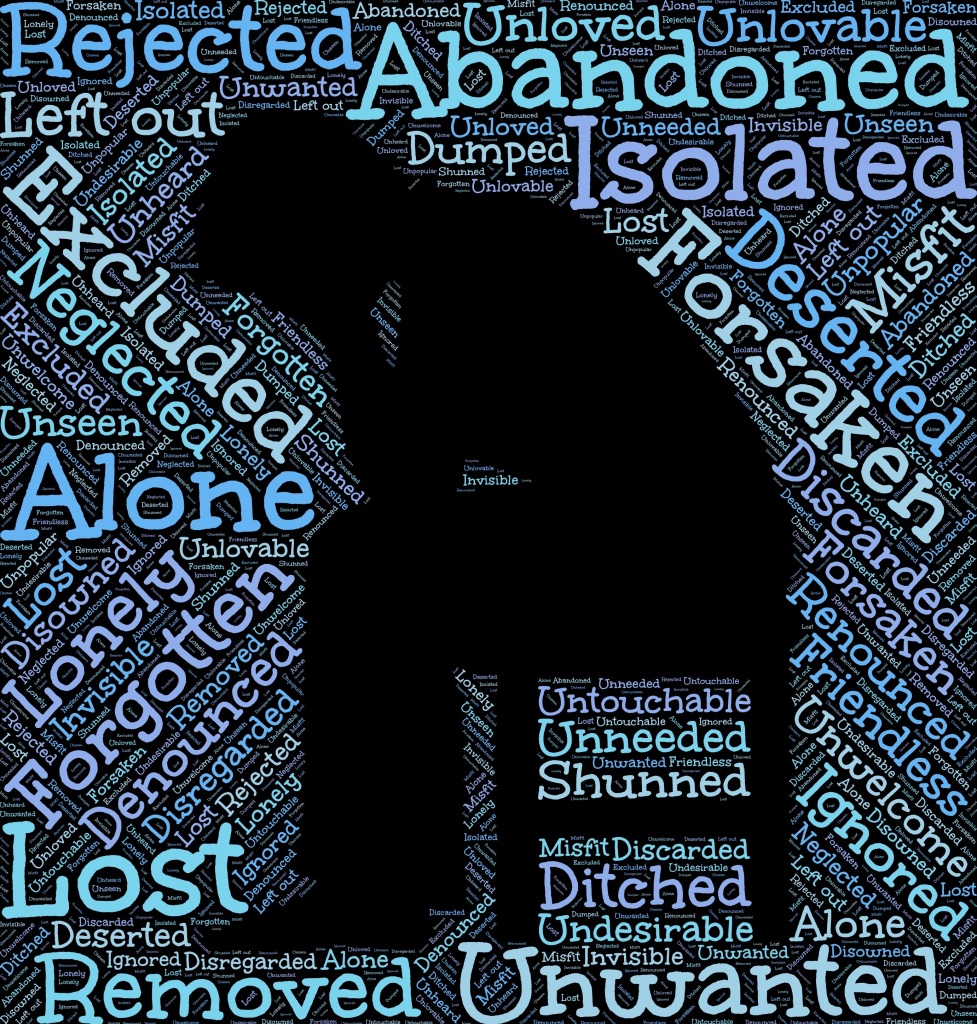

When we think about school shootings, they are much rarer in Canada than in the United States but they do happen here too. Rather than see these as events removed from us we are being called to discipleship in our own community. We might support the anti-bullying work that is a part of many schools. Maybe our discipleship is building relationships with and supporting LGBTQ+ students and others who might sometimes feel like outsiders because of race, ability, or class. Maybe our discipleship is continuing to ensure that guns are not easily available in Canada. Discipleship requires us to take a stand—to speak and act publicly—to create with the holy spirit, the world God envisions. Discipleship often involves saying and doing the things that might make ourselves and others uncomfortable. Once we start on this path, it may lead us to discover other actions that support a safe and flourishing community.

Daring Justice

In scripture, we often find the words justice and righteousness together. Righteousness is about treating others as the image of God and being in right relationship with others. Justice is noticing the vulnerable, offering tangible support that helps for the moment. Justice goes another step and requires us to speak and act to change social structures to prevent injustice.

Sometimes when we look around, the world feels like chaos. There are so many huge overwhelming problems right now. We see war, school shootings, climate change, unmarked graves at residential schools and it feels like we can’t do anything about any of it. As a community of faith there is a tendency to turn inward and focus on ourselves—our survival, our lack of people, our lack of financial resources. But I think this is a story we tell ourselves to avoid the real work that God calls us to. We want to maintain the vision of what we had rather than creating the vision of what could be. We want to be comfortable but, Bold Discipleship and Daring Justice will take us out of our comfort zones.

We know climate change is a real thing—even though there are deny-ers out there. We know that humans are having an impact on the environment and yet it is hard to have a conversation about climate change without becoming mired in the politics. So we don’t talk about it in our church because we don’t want to upset anybody. Some people agree with carbon tax, some people don’t. Some people want more solar and wind power. Some people want more support for the oil and gas industries. Constructive conversation doesn’t happen. We are afraid of the conversation because it might upset someone. Daring justice means that someone is going to be upset. The question is not about us and what’s going to inconvenience us least. The question is what parts of the earth are most impacted by climate change? That’s where our attention and focus need to go. How do we help the earth, as a whole, to flourish? That’s a practical question for how we live. But it also goes towards changing government policy to support and protect the earth.

Justice isn’t short-term bandages. Justice is long-term work that changes the world. I invite us to send our roots deep into our spirituality, to be bold in our discipleship and daring in our justice. May our faith sustain and call us forth.